Toronto Ravines, Invasive Plants, and the Limits of Garden Responsibility

(Dorothy and Patrick Smyth, 2025 – Toronto Master Gardeners)

A review of evidence and implications for urban home gardeners

Introduction

Toronto’s ravine system is one of the city’s defining features. Extending through multiple watersheds and neighbourhoods, the ravines provide flood mitigation, urban cooling, recreation, and important green space in an otherwise dense city. They are rightly valued and widely loved.

In recent years, however, ravines have increasingly been described as ecosystems in crisis. Invasive plants are often identified as a primary cause of ecological decline, and responsibility is sometimes extended—explicitly or implicitly—to individual residents, particularly urban home gardeners and those living near ravines. Gardeners are encouraged to view their planting choices as a major factor influencing ravine health.

This paper steps back from that narrative and asks simpler, evidence-based questions:

1 What do we actually know about the drivers of ecological change in Toronto’s ravines?

2 What does the available evidence support regarding the role of urban home gardeners?

Drawing on long-term ravine studies, wildlife research, and historical analyses, we argue that Toronto’s ravines have been shaped primarily by long-standing disturbance, infrastructure, hydrology, fragmentation, and historical land use. While invasive plants are present and can cause localized problems, existing evidence does not support placing the primary ecological burden for ravine condition on home gardeners.

1. Ravines are Historically Altered Landscapes

Historical research makes it clear that Toronto’s ravines have not been untouched natural systems since European settlement. As documented by urban environmental historians such as Jennifer Bonnell (2019), ravines were heavily logged, farmed, filled, used for dumping, and later reshaped by infrastructure projects throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Most of the built form below Eglinton Avenue was constructed prior to 1946. From the mid-1800s through the mid-20th century, many ravine sections were extensively clear-cut – native and non-native alike. For sustained periods ravines were viewed as hazards or wastelands rather than ecological assets. Streams were channelized, slopes destabilized, soils repeatedly disturbed, dumping was widespread. By the time organized conservation efforts emerged in the mid-twentieth century, ravine ecosystems had already undergone profound and largely irreversible change.

This history refutes the idea that ravine degradation is a recent phenomenon driven primarily by modern invasive species or contemporary gardening practices. Instead, ravines should be understood as urban landscapes that humans have altered over many years, with ecological trajectories shaped well before current debates about native and non-native plants.

2. Evidence from Long-Term Ravine Studies

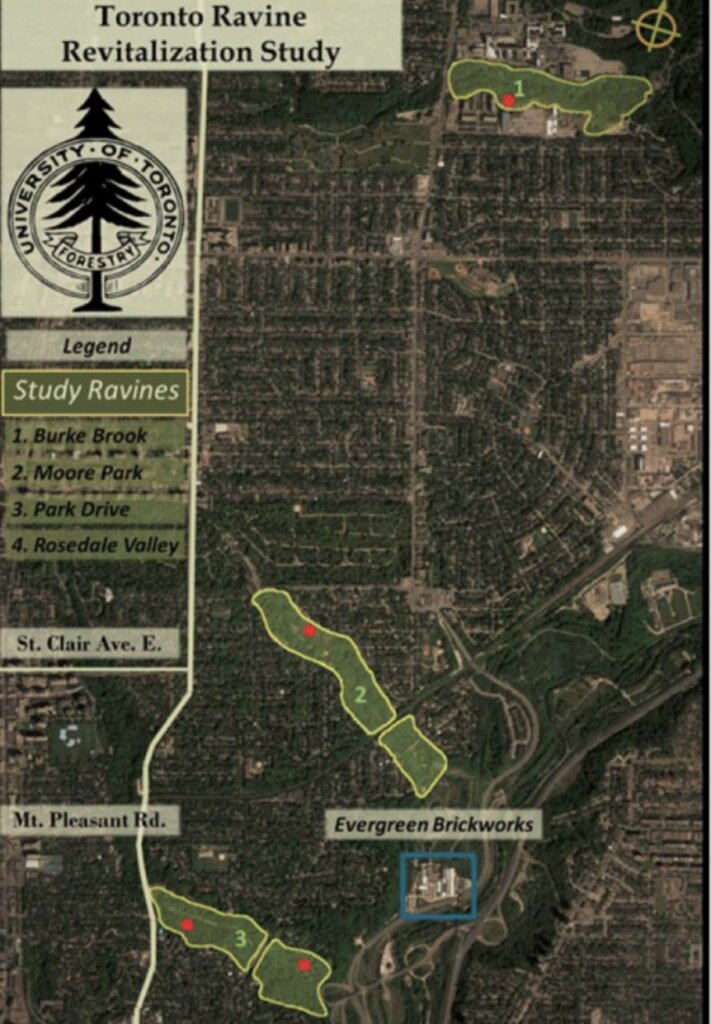

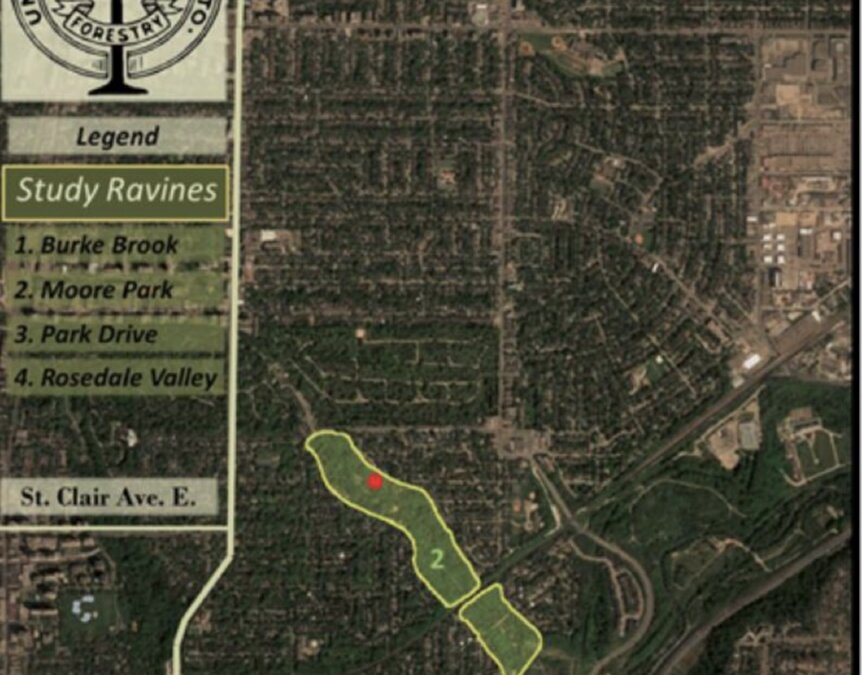

The most frequently cited scientific work on ravine change is the Toronto Ravines Study: 1977–2017 (Davies et al., 2018). This study brings together resurveys of selected ravine plots originally studied in 1977, along with a series of component studies examining plants, birds, mammals, and other indicators.

The study provides valuable insight into site-specific change over four decades, including increased presence of some non-native species at particular locations. However, it is important to understand what the study does—and does not—do.

The Toronto Ravines Study was not designed as a statistically representative, city-wide survey of the entire ravine system. The total area resurveyed is approximately 51 hectares, compared with estimates of total ravine and valley lands ranging from roughly 11,000 to 18,000 hectares, depending on how ravines are defined. The study relies on a limited number of resurveyed plots and component studies conducted at different sites and times, using different methods. It does not provide comprehensive, abundance-based measurements of canopy composition or groundcover across the ravine system as a whole.

As a result, while the study is often cited to support broad claims about ravine-wide ecological decline or invasive dominance, those claims extend beyond what the data can reliably support. Localized change should not be conflated with system-wide patterns.

3. Faunal Studies, Birds, Ravines, and Urban Ecological Limits

Stepniak’s (2017) assessment of mammal and bird communities in selected Toronto ravines provides additional context for understanding ecological limits in urban ravines. By comparing surveys conducted in 1977 and 2017 at four small ravine sites, the study documents limited representation of area-sensitive forest birds and a small assemblage of small mammals.

Birds, along with small mammals and butterflies, are often used as visible and emotionally compelling indicators of ecological health in Toronto’s ravines. Concerns about bird populations are understandable and well founded. Here, birds serve as useful exemplars. However, it is important to be clear about which factors most strongly influence birds in an urban ravine system, and which factors are often overstated.

3.1 Breeding birds in Toronto ravines

Research consistently shows that only a limited set of bird species can breed successfully in narrow, fragmented ravine forests—such as those along Rosedale Valley Road—surrounded by dense urban development. These species tend to be habitat generalists and edge-tolerant birds rather than forest-interior specialists.

Stepniak’s resurvey found that the same small group of area-sensitive forest birds was present in both 1977 and 2017, with only minor change over forty years. This is a critical point: the constraints on ravine bird communities were already firmly established decades ago. There is no evidence in this study that recent changes in plant composition—native or non-native—were associated with detectable changes in breeding bird communities.

In practical terms, most ravines have not supported a full forest bird assemblage for a very long time, regardless of planting choices.

3.2 Historically absent species and realistic expectations

Many bird species that people hope to see in ravines—particularly deep-forest specialists requiring large, continuous tracts of mature canopy—have been largely absent from Toronto’s urban landscape for over a century. Their loss coincided with early deforestation, agricultural clearing, habitat fragmentation, loss of connectivity, and urban expansion, not with recent home-gardening practices.

This sets important limits on what ravine restoration can realistically achieve. Even with extensive native planting, ravines remain narrow, isolated, noisy, and heavily influenced by surrounding urban activity. Expecting plant choice alone to restore historical bird communities risks creating unrealistic expectations and misplaced frustration.

3.3 Documented threats to birds

There are well-documented urban threats to birds that have nothing to do with plant origin. Predation by domestic and feral cats is one of the most significant causes of urban bird mortality.

Another major and well-documented source of bird mortality in Toronto is collisions with glass.

Toronto is internationally recognized as a hotspot for bird–building collisions. According to FLAP Canada (Fatal Light Awareness Program), millions of birds are killed annually in Canada by flying into glass, with Toronto among the most affected cities. Ravines can increase collision risk, as birds use them as movement corridors and then encounter reflective or transparent glass at ravine edges.

This mortality affects both migratory and breeding birds and occurs regardless of whether surrounding vegetation is native or non-native. It represents a direct mortality pressure on bird populations that far exceeds the influence of home-garden-scale plant choices. More information is available at https://flap.org.

3.4 What this means for home gardeners

Bird populations in Toronto ravines are shaped primarily by habitat fragmentation and limited forest size, long-standing historical losses, urban disturbance (noise, lighting, human activity), and major mortality sources such as window collisions and predation.

While vegetation structure can matter locally, there is no evidence that invasive plants—or the actions of urban home gardeners—are the primary driver of bird declines in ravines.

4. Invasive Plants and the Question of Scale

Ecological impacts of invasive species are known to be highly context-dependent and scale-sensitive, particularly in urban systems characterized by chronic disturbance.

Invasive plants can influence ecological processes, particularly in disturbed environments. However, their impacts are highly context-dependent and interact with other drivers such as altered hydrology, soil compaction, canopy disturbance (including widespread ash mortality), and climate stress.

A key limitation in Toronto is the absence of a city-wide dataset measuring plant abundance, cover, or biomass across ravines. Most available data consist of species-occurrence records or localized surveys. Presence alone does not equal dominance or ecological impact, yet presence-based information is often used to support strong claims.

Without abundance-based, system-wide measurements, assertions that invasive plants are the primary drivers of ravine degradation remain speculative.

5. Pathways of Introduction and the Role of Gardeners

The claim that invasive ravine plants primarily originate from contemporary home gardens is often asserted but rarely demonstrated at the scale of the ravine system. Historical evidence shows that many widespread non-native species arrived through early horticulture, agriculture, transportation corridors, fill material, and watershed dispersal—often many decades ago.

Municipal planting practices also played a role. For much of the mid-20th century, Norway maple was widely planted by the City of Toronto in streetscapes, parks, and along ravine edges, contributing to its present distribution independent of contemporary home gardening.

Many of the most disruptive species are no longer widely sold, and existing ravine populations are largely self-sustaining. While gardeners near ravines should act responsibly, attributing ravine-scale ecological outcomes to individual planting decisions overlooks the dominant influence of historical land use and ongoing urban disturbance.

6. Implications for Ravine Management and Messaging

Taken together, the literature suggests that Toronto’s ravines function as novel urban ecosystems, shaped by centuries of alteration and maintained under persistent urban pressures. Invasive plants are one factor among many impacting our ravine ecosystems. Current evidence does not support narratives that place primary responsibility for invasive plant introductions in ravines on urban home gardeners.

Effective ravine stewardship should emphasize watershed-scale management, infrastructure design, canopy resilience, erosion control, control of illegal dumping, bird-safe building practices, and realistic ecological goals—rather than moralizing individual gardening choices.

Conclusion

Toronto’s ravines are ecologically valuable, but they are neither pristine nor primarily shaped by recent gardening practices. Historical transformation, urbanization, and structural disturbance have played dominant roles in shaping present conditions. While invasive plants warrant thoughtful, site-specific management, assigning disproportionate ecological burden to urban home gardeners is not supported by the available evidence and risks undermining constructive engagement with urban nature.

References (selected)

Bonnell, J. (2019). Remembering and Forgetting in Toronto’s Ravines.

Davies, E., et al. (2018). Toronto Ravines Study: 1977–2017. University of Toronto / Smith Lab.

Stepniak, A. (2017). Ecological Integrity of Mammals and Birds in Toronto’s Ravines.

FLAP Canada (Fatal Light Awareness Program). https://flap.org

Methodological Note on Abundance

Abundance values are derived from a scaled frequency and persistence index (Combined_abund_scaled) based on repeated species records across multiple sites and years within the Toronto region. This metric does not represent measured cover, density, or biomass. Instead, it reflects how consistently a species is recorded across space and time, providing a proxy for relative persistence. Such indices are commonly used in urban and historical ecology where comprehensive plot-based inventories are unavailable. Values are used here for comparative purposes only and are not intended to infer dominance at individual sites.

Appendices

Appendices A–C provide ranked lists of the most abundant plant species in a Toronto-wide dataset. Although these data are not specific to ravine vegetation, they offer broader ecological and historical context for this paper by distinguishing species that are merely present from those that are widespread, persistent, and long-established across the urban landscape. Together, the three lists (all plants, non-native plants, and native plants) help ground discussion of invasive impact, introduction pathways, and gardener responsibility in observable Toronto-wide patterns rather than anecdote. The Toronto-wide plant dataset used for these appendices draws on aggregated occurrence records and abundance proxies compiled for urban ecological analysis; methodological details and validation of this approach are described in Cadotte et al. (2021), available at https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2688-8319.12036

Appendix A: Top 25 Most Abundant Plants (Toronto-wide Dataset)

This appendix lists the 25 most abundant plant species in the Toronto-wide dataset, ranked by a scaled abundance metric. While the dataset is not ravine-specific, these species represent those most persistent and frequently recorded across the broader urban landscape and provide context for interpretations of ravine vegetation.

| SCIENTIFIC_NAME | ENGLISH_COMMON_NAME | Combined_abund_scaled |

| Symphyotrichum cordifolium | Heart-leaved Aster | 100 |

| Rhus typhina | Staghorn Sumac | 96 |

| Trillium grandiflorum | White Trillium | 92 |

| Symphyotrichum novae-angliae | New England Aster | 83 |

| Anemone canadensis | Canada anemone | 81 |

| Equisetum arvense | Field Horsetail | 81 |

| Potentilla anserina | Silverweed | 81 |

| Acer negundo | Manitoba Maple | 75 |

| Cornus sericea | Red-osier Dogwood | 73 |

| Vincetoxicum rossicum | European Swallow-wort | 70 |

| Daucus carota | Wild Carrot | 68 |

| Rhamnus cathartica | Common Buckthorn | 67 |

| Potentilla supina | Bushy Cinquefoil | 64 |

| Epipactis helleborine | Eastern Helleborine | 64 |

| Tussilago farfara | Colt’s-foot | 63 |

| Linaria vulgaris | Butter-and-eggs | 62 |

| Vicia cracca | Tufted Vetch | 62 |

| Cichorium intybus | Chicory | 61 |

| Symphyotrichum ericoides | White Heath Aster | 60 |

| Solanum dulcamara | Bittersweet Nightshade | 60 |

| Salsola kali | Common Saltwort | 59 |

| Viburnum opulus | Highbush Cranberry | 59 |

| Sanguinaria canadensis | Bloodroot | 57 |

| Maianthemum stellatum | Star-flowered False Solomon’s Seal | 57 |

| Ageratina altissima | Common White Snakeroot | 57 |

Appendix B: Top 25 Most Abundant Non-native Plants (Toronto-wide Dataset)

This appendix presents the 25 most abundant non-native plant species in the Toronto-wide dataset. Recorded year of introduction and cultivation status are included where available, helping distinguish long-established species from more recent or actively cultivated introductions.

| SCIENTIFIC_NAME | ENGLISH_COMMON_NAME | Year_first_record_exotic | Cultivated | Combined_abund_scaled |

| Vincetoxicum rossicum | European Swallow-wort | 70 | ||

| Daucus carota | Wild Carrot | 68 | ||

| Rhamnus cathartica | Common Buckthorn | 67 | ||

| Epipactis helleborine | Eastern Helleborine | 64 | ||

| Tussilago farfara | Colt’s-foot | 63 | ||

| Vicia cracca | Tufted Vetch | 1893 | 62 | |

| Linaria vulgaris | Butter-and-eggs | 62 | ||

| Cichorium intybus | Chicory | 1885 | 61 | |

| Solanum dulcamara | Bittersweet Nightshade | 1895 | 60 | |

| Salsola kali | Common Saltwort | 59 | ||

| Acer platanoides | Norway Maple | 56 | ||

| Ranunculus acris | Tall Buttercup | 55 | ||

| Hesperis matronalis | Dame’s Rocket | 1906 | 52 | |

| Alliaria petiolata | Garlic Mustard | 49 | ||

| Trifolium pratense | Red Clover | 49 | ||

| Lythrum salicaria | Purple Loosestrife | 1928 | 48 | |

| Saponaria officinalis | Bouncing-bet | 48 | ||

| Hypericum perforatum | Common St. John’s-wort | 48 | ||

| Echium vulgare | Common Viper’s Bugloss | 48 | ||

| Taraxacum officinale | Common Dandelion | 48 | ||

| Cypripedium calceolus | Lady’s slipper orchid | U | 47 | |

| Reynoutria japonica | Japanese knotweed | 46 | ||

| Elymus repens | Creeping Wildrye | 45 | ||

| Cirsium arvense | Creeping Thistle | 1892 | 43 | |

| Plantago major | Common Plantain | 42 |

Appendix C: Top 25 Most Abundant Native Plants (Toronto-wide Dataset)

This appendix lists the 25 most abundant native plant species in the Toronto-wide dataset. These species form the core of the region’s persistent native flora and provide a comparator for evaluating claims about displacement by non-native plants.

| SCIENTIFIC_NAME | ENGLISH_COMMON_NAME | Combined_abund_scaled |

| Symphyotrichum cordifolium | Heart-leaved Aster | 100 |

| Rhus typhina | Staghorn Sumac | 96 |

| Trillium grandiflorum | White Trillium | 92 |

| Symphyotrichum novae-angliae | New England Aster | 83 |

| Equisetum arvense | Field Horsetail | 81 |

| Anemone canadensis | Canada anemone | 81 |

| Potentilla anserina | Silverweed | 81 |

| Acer negundo | Manitoba Maple | 75 |

| Cornus sericea | Red-osier Dogwood | 73 |

| Potentilla supina | Bushy Cinquefoil | 64 |

| Symphyotrichum ericoides | White Heath Aster | 60 |

| Viburnum opulus | Highbush Cranberry | 59 |

| Maianthemum stellatum | Star-flowered False Solomon’s Seal | 57 |

| Sanguinaria canadensis | Bloodroot | 57 |

| Ageratina altissima | Common White Snakeroot | 57 |

| Symphyotrichum ciliatum | Rayless Alkali Aster | 56 |

| Prunus virginiana | Choke Cherry | 56 |

| Asclepias syriaca | Common Milkweed | 55 |

| Viburnum acerifolium | Maple-leaved Viburnum | 55 |

| Geranium maculatum | Spotted Geranium | 55 |

| Prunus serotina | Black Cherry | 55 |

| Hamamelis virginiana | American Witch-hazel | 54 |

| Arisaema triphyllum | Jack-in-the-pulpit | 54 |

| Impatiens capensis | Spotted Jewelweed | 54 |

| Acer saccharum | Sugar Maple | 54 |

Recent Comments